Item 7. Bank of America Corporation and Subsidiaries Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations | ||||

Table of Contents | ||

Page | ||

Bank of America 2011 1 | ||

2 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 3 | ||

Table 1 | Selected Financial Data | |||||||

(Dollars in millions, except per share information) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Income statement | ||||||||

Revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) (1) | $ | 94,426 | $ | 111,390 | ||||

Net income (loss) | 1,446 | (2,238 | ) | |||||

Net income, excluding goodwill impairment charges (2) | 4,630 | 10,162 | ||||||

Diluted earnings (loss) per common share (3) | 0.01 | (0.37 | ) | |||||

Diluted earnings per common share, excluding goodwill impairment charges (2) | 0.32 | 0.86 | ||||||

Dividends paid per common share | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||||

Performance ratios | ||||||||

Return on average assets | 0.06 | % | n/m | |||||

Return on average assets, excluding goodwill impairment charges (2) | 0.20 | 0.42 | % | |||||

Return on average tangible shareholders’ equity (1) | 0.96 | n/m | ||||||

Return on average tangible shareholders’ equity, excluding goodwill impairment charges (1, 2) | 3.08 | 7.11 | ||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) (1) | 85.01 | 74.61 | ||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis), excluding goodwill impairment charges (1, 2) | 81.64 | 63.48 | ||||||

Asset quality | ||||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses at December 31 | $ | 33,783 | $ | 41,885 | ||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses as a percentage of total loans and leases outstanding at December 31 (4) | 3.68 | % | 4.47 | % | ||||

Nonperforming loans, leases and foreclosed properties at December 31 (4) | $ | 27,708 | $ | 32,664 | ||||

Net charge-offs | 20,833 | 34,334 | ||||||

Net charge-offs as a percentage of average loans and leases outstanding (4) | 2.24 | % | 3.60 | % | ||||

Net charge-offs as a percentage of average loans and leases outstanding excluding purchased credit-impaired loans (4) | 2.32 | 3.73 | ||||||

Ratio of the allowance for loan and lease losses at December 31 to net charge-offs | 1.62 | 1.22 | ||||||

Ratio of the allowance for loan and lease losses at December 31 to net charge-offs excluding purchased credit-impaired loans | 1.22 | 1.04 | ||||||

Balance sheet at year end | ||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 926,200 | $ | 940,440 | ||||

Total assets | 2,129,046 | 2,264,909 | ||||||

Total deposits | 1,033,041 | 1,010,430 | ||||||

Total common shareholders’ equity | 211,704 | 211,686 | ||||||

Total shareholders’ equity | 230,101 | 228,248 | ||||||

Capital ratios at year end | ||||||||

Tier 1 common capital | 9.86 | % | 8.60 | % | ||||

Tier 1 capital | 12.40 | 11.24 | ||||||

Total capital | 16.75 | 15.77 | ||||||

Tier 1 leverage | 7.53 | 7.21 | ||||||

(1) | Fully taxable-equivalent (FTE) basis, return on average tangible shareholders’ equity and the efficiency ratio are non-GAAP financial measures. Other companies may define or calculate these measures differently. For additional information on these measures and ratios, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15, and for a corresponding reconciliation to GAAP financial measures, see Table XV. |

(2) | Net income (loss), diluted earnings (loss) per common share, return on average assets, return on average tangible shareholders’ equity and the efficiency ratio have been calculated excluding the impact of goodwill impairment charges of $3.2 billion and $12.4 billion in 2011 and 2010, and accordingly, these are non-GAAP financial measures. For additional information on these measures and ratios, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15, and for a corresponding reconciliation to GAAP financial measures, see Table XV. |

(3) | Due to a net loss applicable to common shareholders in 2010, the impact of antidilutive equity instruments was excluded from diluted earnings (loss) per share and average diluted common shares. |

(4) | Balances and ratios do not include loans accounted for under the fair value option. For additional exclusions from nonperforming loans, leases and foreclosed properties, see Nonperforming Consumer Loans and Foreclosed Properties Activity on page 69 and corresponding Table 36, and Nonperforming Commercial Loans, Leases and Foreclosed Properties Activity on page 77 and corresponding Table 45. |

4 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 5 | ||

6 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 7 | ||

Table 2 | Summary Income Statement | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) (1) | $ | 45,588 | $ | 52,693 | ||||

Noninterest income | 48,838 | 58,697 | ||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) (1) | 94,426 | 111,390 | ||||||

Provision for credit losses | 13,410 | 28,435 | ||||||

Goodwill impairment | 3,184 | 12,400 | ||||||

All other noninterest expense | 77,090 | 70,708 | ||||||

Income (loss) before income taxes | 742 | (153 | ) | |||||

Income tax expense (benefit) (FTE basis) (1) | (704 | ) | 2,085 | |||||

Net income (loss) | 1,446 | (2,238 | ) | |||||

Preferred stock dividends | 1,361 | 1,357 | ||||||

Net income (loss) applicable to common shareholders | $ | 85 | $ | (3,595 | ) | |||

Per common share information | ||||||||

Earnings (loss) | $ | 0.01 | $ | (0.37 | ) | |||

Diluted earnings (loss) | 0.01 | (0.37 | ) | |||||

(1) | Fully taxable-equivalent (FTE) basis is a non-GAAP financial measure. Other companies may define or calculate this measure differently. For more information on this measure, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15, and for a corresponding reconciliation to a GAAP financial measure, see Table XV. |

8 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 3 | Business Segment Results | |||||||||||||||

Total Revenue (1) | Net Income (Loss) | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Consumer & Business Banking (CBB) | $ | 32,873 | $ | 38,181 | $ | 7,452 | $ | (5,134 | ) | |||||||

Consumer Real Estate Services (CRES) | (3,154 | ) | 10,329 | (19,473 | ) | (8,897 | ) | |||||||||

Global Banking | 17,318 | 17,748 | 6,047 | 4,891 | ||||||||||||

Global Markets | 14,785 | 19,118 | 985 | 4,246 | ||||||||||||

Global Wealth & Investment Management (GWIM) | 17,396 | 16,291 | 1,672 | 1,353 | ||||||||||||

All Other | 15,208 | 9,723 | 4,763 | 1,303 | ||||||||||||

Total FTE basis | 94,426 | 111,390 | 1,446 | (2,238 | ) | |||||||||||

FTE adjustment | (972 | ) | (1,170 | ) | — | — | ||||||||||

Total Consolidated | $ | 93,454 | $ | 110,220 | $ | 1,446 | $ | (2,238 | ) | |||||||

(1) | Total revenue is net of interest expense and is on a FTE basis which is a non-GAAP financial measure. For more information on this measure, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15, and for a corresponding reconciliation to a GAAP financial measure, see Table XV. |

Bank of America 2011 9 | ||

Table 4 | Noninterest Income | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Card income | $ | 7,184 | $ | 8,108 | ||||

Service charges | 8,094 | 9,390 | ||||||

Investment and brokerage services | 11,826 | 11,622 | ||||||

Investment banking income | 5,217 | 5,520 | ||||||

Equity investment income | 7,360 | 5,260 | ||||||

Trading account profits | 6,697 | 10,054 | ||||||

Mortgage banking income (loss) | (8,830 | ) | 2,734 | |||||

Insurance income | 1,346 | 2,066 | ||||||

Gains on sales of debt securities | 3,374 | 2,526 | ||||||

Other income | 6,869 | 2,384 | ||||||

Net impairment losses recognized in earnings on available-for-sale debt securities | (299 | ) | (967 | ) | ||||

Total noninterest income | $ | 48,838 | $ | 58,697 | ||||

Ÿ | Card income decreased $924 million primarily due to the implementation of new interchange fee rules under the Durbin Amendment, which became effective on October 1, 2011 and the CARD Act provisions that were implemented during 2010. |

Ÿ | Service charges decreased $1.3 billion largely due to the impact of overdraft policy changes in conjunction with Regulation E, which became effective in the third quarter of 2010. |

Ÿ | Equity investment income increased $2.1 billion. The results for 2011 included $6.5 billion of gains on the sale of CCB shares, $836 million of CCB dividends and a $377 million gain on the sale of our investment in BlackRock, Inc. (BlackRock), partially offset by $1.1 billion of impairment charges on our merchant services joint venture. The prior year included $2.5 billion of net gains which included the sales of certain strategic investments, $2.3 billion of gains in our Global Principal Investments (GPI) portfolio which included both cash gains and fair value adjustments, and $535 million of CCB dividends. |

Ÿ | Trading account profits decreased $3.4 billion primarily due to adverse market conditions and extreme volatility in the credit markets compared to the prior year. DVA gains, net of hedges, on derivatives were $1.0 billion in 2011 compared to $262 million in 2010 as a result of a widening of our credit spreads. In conjunction with regulatory reform measures Global Markets exited its stand-alone proprietary trading business as of June 30, 2011. Proprietary trading revenue was $434 million for the |

Ÿ | Mortgage banking income decreased $11.6 billion primarily due to an $8.8 billion increase in the representations and warranties provision which was largely related to the BNY Mellon Settlement. Also contributing to the decline was lower production income due to a reduction in new loan origination volumes partially offset by an increase in servicing income. |

Ÿ | Other income increased $4.5 billion primarily due to positive fair value adjustments of $3.3 billion related to widening of our own credit spreads on structured liabilities compared to $18 million in 2010. In addition, 2011 included a $771 million gain on the sale of Balboa as well as a $1.2 billion gain on the exchange of certain trust preferred securities for common stock and debt. |

10 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 5 | Noninterest Expense | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Personnel | $ | 36,965 | $ | 35,149 | ||||

Occupancy | 4,748 | 4,716 | ||||||

Equipment | 2,340 | 2,452 | ||||||

Marketing | 2,203 | 1,963 | ||||||

Professional fees | 3,381 | 2,695 | ||||||

Amortization of intangibles | 1,509 | 1,731 | ||||||

Data processing | 2,652 | 2,544 | ||||||

Telecommunications | 1,553 | 1,416 | ||||||

Other general operating | 21,101 | 16,222 | ||||||

Goodwill impairment | 3,184 | 12,400 | ||||||

Merger and restructuring charges | 638 | 1,820 | ||||||

Total noninterest expense | $ | 80,274 | $ | 83,108 | ||||

Bank of America 2011 11 | ||

Table 6 | Selected Balance Sheet Data | |||||||||||||||

December 31 | Average Balance | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Assets | ||||||||||||||||

Federal funds sold and securities borrowed or purchased under agreements to resell | $ | 211,183 | $ | 209,616 | $ | 245,069 | $ | 256,943 | ||||||||

Trading account assets | 169,319 | 194,671 | 187,340 | 213,745 | ||||||||||||

Debt securities | 311,416 | 338,054 | 337,120 | 323,946 | ||||||||||||

Loans and leases | 926,200 | 940,440 | 938,096 | 958,331 | ||||||||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses | (33,783 | ) | (41,885 | ) | (37,623 | ) | (45,619 | ) | ||||||||

All other assets | 544,711 | 624,013 | 626,320 | 732,260 | ||||||||||||

Total assets | $ | 2,129,046 | $ | 2,264,909 | $ | 2,296,322 | $ | 2,439,606 | ||||||||

Liabilities | ||||||||||||||||

Deposits | $ | 1,033,041 | $ | 1,010,430 | $ | 1,035,802 | $ | 988,586 | ||||||||

Federal funds purchased and securities loaned or sold under agreements to repurchase | 214,864 | 245,359 | 272,375 | 353,653 | ||||||||||||

Trading account liabilities | 60,508 | 71,985 | 84,689 | 91,669 | ||||||||||||

Commercial paper and other short-term borrowings | 35,698 | 59,962 | 51,894 | 76,676 | ||||||||||||

Long-term debt | 372,265 | 448,431 | 421,229 | 490,497 | ||||||||||||

All other liabilities | 182,569 | 200,494 | 201,238 | 205,290 | ||||||||||||

Total liabilities | 1,898,945 | 2,036,661 | 2,067,227 | 2,206,371 | ||||||||||||

Shareholders’ equity | 230,101 | 228,248 | 229,095 | 233,235 | ||||||||||||

Total liabilities and shareholders’ equity | $ | 2,129,046 | $ | 2,264,909 | $ | 2,296,322 | $ | 2,439,606 | ||||||||

12 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 13 | ||

Table 7 | Five Year Summary of Selected Financial Data | |||||||||||||||||||

(In millions, except per share information) | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | |||||||||||||||

Income statement | ||||||||||||||||||||

Net interest income | $ | 44,616 | $ | 51,523 | $ | 47,109 | $ | 45,360 | $ | 34,441 | ||||||||||

Noninterest income | 48,838 | 58,697 | 72,534 | 27,422 | 32,392 | |||||||||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense | 93,454 | 110,220 | 119,643 | 72,782 | 66,833 | |||||||||||||||

Provision for credit losses | 13,410 | 28,435 | 48,570 | 26,825 | 8,385 | |||||||||||||||

Goodwill impairment | 3,184 | 12,400 | — | — | — | |||||||||||||||

Merger and restructuring charges | 638 | 1,820 | 2,721 | 935 | 410 | |||||||||||||||

All other noninterest expense (1) | 76,452 | 68,888 | 63,992 | 40,594 | 37,114 | |||||||||||||||

Income (loss) before income taxes | (230 | ) | (1,323 | ) | 4,360 | 4,428 | 20,924 | |||||||||||||

Income tax expense (benefit) | (1,676 | ) | 915 | (1,916 | ) | 420 | 5,942 | |||||||||||||

Net income (loss) | 1,446 | (2,238 | ) | 6,276 | 4,008 | 14,982 | ||||||||||||||

Net income (loss) applicable to common shareholders | 85 | (3,595 | ) | (2,204 | ) | 2,556 | 14,800 | |||||||||||||

Average common shares issued and outstanding | 10,143 | 9,790 | 7,729 | 4,592 | 4,424 | |||||||||||||||

Average diluted common shares issued and outstanding (2) | 10,255 | 9,790 | 7,729 | 4,596 | 4,463 | |||||||||||||||

Performance ratios | ||||||||||||||||||||

Return on average assets | 0.06 | % | n/m | 0.26 | % | 0.22 | % | 0.94 | % | |||||||||||

Return on average common shareholders’ equity | 0.04 | n/m | n/m | 1.80 | 11.08 | |||||||||||||||

Return on average tangible common shareholders’ equity (3) | 0.06 | n/m | n/m | 4.72 | 26.19 | |||||||||||||||

Return on average tangible shareholders’ equity (3) | 0.96 | n/m | 4.18 | 5.19 | 25.13 | |||||||||||||||

Total ending equity to total ending assets | 10.81 | 10.08 | % | 10.38 | 9.74 | 8.56 | ||||||||||||||

Total average equity to total average assets | 9.98 | 9.56 | 10.01 | 8.94 | 8.53 | |||||||||||||||

Dividend payout | n/m | n/m | n/m | n/m | 72.26 | |||||||||||||||

Per common share data | ||||||||||||||||||||

Earnings (loss) | $ | 0.01 | $ | (0.37 | ) | $ | (0.29 | ) | $ | 0.54 | $ | 3.32 | ||||||||

Diluted earnings (loss) (2) | 0.01 | (0.37 | ) | (0.29 | ) | 0.54 | 3.29 | |||||||||||||

Dividends paid | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 2.24 | 2.40 | |||||||||||||||

Book value | 20.09 | 20.99 | 21.48 | 27.77 | 32.09 | |||||||||||||||

Tangible book value (3) | 12.95 | 12.98 | 11.94 | 10.11 | 12.71 | |||||||||||||||

Market price per share of common stock | ||||||||||||||||||||

Closing | $ | 5.56 | $ | 13.34 | $ | 15.06 | $ | 14.08 | $ | 41.26 | ||||||||||

High closing | 15.25 | 19.48 | 18.59 | 45.03 | 54.05 | |||||||||||||||

Low closing | 4.99 | 10.95 | 3.14 | 11.25 | 41.10 | |||||||||||||||

Market capitalization | $ | 58,580 | $ | 134,536 | $ | 130,273 | $ | 70,645 | $ | 183,107 | ||||||||||

Average balance sheet | ||||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 938,096 | $ | 958,331 | $ | 948,805 | $ | 910,871 | $ | 776,154 | ||||||||||

Total assets | 2,296,322 | 2,439,606 | 2,443,068 | 1,843,985 | 1,602,073 | |||||||||||||||

Total deposits | 1,035,802 | 988,586 | 980,966 | 831,157 | 717,182 | |||||||||||||||

Long-term debt | 421,229 | 490,497 | 446,634 | 231,235 | 169,855 | |||||||||||||||

Common shareholders’ equity | 211,709 | 212,686 | 182,288 | 141,638 | 133,555 | |||||||||||||||

Total shareholders’ equity | 229,095 | 233,235 | 244,645 | 164,831 | 136,662 | |||||||||||||||

Asset quality (4) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Allowance for credit losses (5) | $ | 34,497 | $ | 43,073 | $ | 38,687 | $ | 23,492 | $ | 12,106 | ||||||||||

Nonperforming loans, leases and foreclosed properties (6) | 27,708 | 32,664 | 35,747 | 18,212 | 5,948 | |||||||||||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses as a percentage of total loans and leases outstanding (6) | 3.68 | % | 4.47 | % | 4.16 | % | 2.49 | % | 1.33 | % | ||||||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses as a percentage of total nonperforming loans and leases (6) | 135 | 136 | 111 | 141 | 207 | |||||||||||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses as a percentage of total nonperforming loans and leases excluding the PCI loan portfolio (6) | 101 | 116 | 99 | 136 | n/a | |||||||||||||||

Amounts included in allowance that are excluded from nonperforming loans (7) | $ | 17,490 | $ | 22,908 | $ | 17,690 | $ | 11,679 | $ | 6,520 | ||||||||||

Allowances as a percentage of total nonperforming loans and leases excluding the amounts included in the allowance that are excluded from nonperforming loans (7) | 65 | % | 62 | % | 58 | % | 70 | % | 91 | % | ||||||||||

Net charge-offs | $ | 20,833 | $ | 34,334 | $ | 33,688 | $ | 16,231 | $ | 6,480 | ||||||||||

Net charge-offs as a percentage of average loans and leases outstanding (6) | 2.24 | % | 3.60 | % | 3.58 | % | 1.79 | % | 0.84 | % | ||||||||||

Nonperforming loans and leases as a percentage of total loans and leases outstanding (6) | 2.74 | 3.27 | 3.75 | 1.77 | 0.64 | |||||||||||||||

Nonperforming loans, leases and foreclosed properties as a percentage of total loans, leases and foreclosed properties (6) | 3.01 | 3.48 | 3.98 | 1.96 | 0.68 | |||||||||||||||

Ratio of the allowance for loan and lease losses at December 31 to net charge-offs | 1.62 | 1.22 | 1.10 | 1.42 | 1.79 | |||||||||||||||

Capital ratios (year end) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Risk-based capital: | ||||||||||||||||||||

Tier 1 common | 9.86 | % | 8.60 | % | 7.81 | % | 4.80 | % | 4.93 | % | ||||||||||

Tier 1 | 12.40 | 11.24 | 10.40 | 9.15 | 6.87 | |||||||||||||||

Total | 16.75 | 15.77 | 14.66 | 13.00 | 11.02 | |||||||||||||||

Tier 1 leverage | 7.53 | 7.21 | 6.88 | 6.44 | 5.04 | |||||||||||||||

Tangible equity (3) | 7.54 | 6.75 | 6.40 | 5.11 | 3.73 | |||||||||||||||

Tangible common equity (3) | 6.64 | 5.99 | 5.56 | 2.93 | 3.46 | |||||||||||||||

(1) | Excludes merger and restructuring charges and goodwill impairment charges. |

(2) | Due to a net loss applicable to common shareholders for 2010 and 2009, the impact of antidilutive equity instruments was excluded from diluted earnings (loss) per share and average diluted common shares. |

(3) | Tangible equity ratios and tangible book value per share of common stock are non-GAAP financial measures. Other companies may define or calculate these measures differently. For additional information on these ratios and corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and Table XV. |

(4) | For more information on the impact of the PCI loan portfolio on asset quality, see Consumer Portfolio Credit Risk Management on page 58 and Commercial Portfolio Credit Risk Management on page 71. |

(5) | Includes the allowance for loan and lease losses and the reserve for unfunded lending commitments. |

(6) | Balances and ratios do not include loans accounted for under the fair value option. For additional exclusions on nonperforming loans, leases and foreclosed properties, see Nonperforming Consumer Loans and Foreclosed Properties Activity on page 69 and corresponding Table 36 and Nonperforming Commercial Loans, Leases and Foreclosed Properties Activity on page 77 and corresponding Table 45. |

(7) | Amounts included in allowance that are excluded from nonperforming loans primarily include amounts allocated to U.S. credit card and unsecured consumer lending portfolios in CBB, PCI loans and the non-U.S. credit card portfolio in All Other. |

14 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Ÿ | Return on average tangible common shareholders’ equity measures our earnings contribution as a percentage of adjusted common shareholders’ equity plus any Common Equivalent Securities (CES). The tangible common equity ratio represents adjusted common shareholders’ equity plus any CES divided by total assets less goodwill and intangible assets (excluding |

Ÿ | ROTE measures our earnings contribution as a percentage of adjusted average total shareholders’ equity. The tangible equity ratio represents adjusted total shareholders’ equity divided by total assets less goodwill and intangible assets (excluding MSRs), net of related deferred tax liabilities. |

Ÿ | Tangible book value per common share represents adjusted ending common shareholders’ equity divided by ending common shares outstanding. |

Ÿ | Return on average economic capital for the segments is calculated as net income, adjusted for cost of funds and earnings credits and certain expenses related to intangibles, divided by average economic capital. |

Ÿ | Economic capital represents allocated equity less goodwill and a percentage of intangible assets (excluding MSRs). |

Table 8 | Five Year Supplemental Financial Data | |||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions, except per share information) | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | |||||||||||||||

Fully taxable-equivalent basis data | ||||||||||||||||||||

Net interest income | $ | 45,588 | $ | 52,693 | $ | 48,410 | $ | 46,554 | $ | 36,190 | ||||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense | 94,426 | 111,390 | 120,944 | 73,976 | 68,582 | |||||||||||||||

Net interest yield | 2.48 | % | 2.78 | % | 2.65 | % | 2.98 | % | 2.60 | % | ||||||||||

Efficiency ratio | 85.01 | 74.61 | 55.16 | 56.14 | 54.71 | |||||||||||||||

Performance ratios, excluding goodwill impairment charges (1) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Per common share information | ||||||||||||||||||||

Earnings | $ | 0.32 | $ | 0.87 | ||||||||||||||||

Diluted earnings | 0.32 | 0.86 | ||||||||||||||||||

Efficiency ratio | 81.64 | % | 63.48 | % | ||||||||||||||||

Return on average assets | 0.20 | 0.42 | ||||||||||||||||||

Return on average common shareholders’ equity | 1.54 | 4.14 | ||||||||||||||||||

Return on average tangible common shareholders’ equity | 2.46 | 7.03 | ||||||||||||||||||

Return on average tangible shareholders’ equity | 3.08 | 7.11 | ||||||||||||||||||

(1) | Performance ratios are calculated excluding the impact of goodwill impairment charges of $3.2 billion and $12.4 billion recorded during 2011 and 2010. |

Bank of America 2011 15 | ||

Table 9 | Core Net Interest Income | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | ||||||||

As reported (1) | $ | 45,588 | $ | 52,693 | ||||

Impact of market-based net interest income (2) | (3,813 | ) | (4,430 | ) | ||||

Core net interest income | 41,775 | 48,263 | ||||||

Average earning assets | ||||||||

As reported | 1,834,659 | 1,897,573 | ||||||

Impact of market-based earning assets (2) | (448,776 | ) | (512,804 | ) | ||||

Core average earning assets | $ | 1,385,883 | $ | 1,384,769 | ||||

Net interest yield contribution (FTE basis) | ||||||||

As reported (1) | 2.48 | % | 2.78 | % | ||||

Impact of market-based activities (2) | 0.53 | 0.71 | ||||||

Core net interest yield on earning assets | 3.01 | % | 3.49 | % | ||||

(1) | Net interest income and net interest yield include fees earned on overnight deposits placed with the Federal Reserve of $186 million and $368 million for 2011 and 2010. |

(2) | Represents the impact of market-based amounts included in Global Markets. |

16 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Deposits | Card Services | Business Banking | Total Consumer & Business Banking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 8,471 | $ | 8,278 | $ | 11,502 | $ | 14,408 | $ | 1,404 | $ | 1,612 | $ | 21,377 | $ | 24,298 | (12 | )% | |||||||||||||||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Card income | — | — | 6,286 | 7,054 | — | — | 6,286 | 7,054 | (11 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Service charges | 3,995 | 5,057 | — | — | 523 | 527 | 4,518 | 5,584 | (19 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

All other income | 223 | 227 | 328 | 851 | 141 | 167 | 692 | 1,245 | (44 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total noninterest income | 4,218 | 5,284 | 6,614 | 7,905 | 664 | 694 | 11,496 | 13,883 | (17 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 12,689 | 13,562 | 18,116 | 22,313 | 2,068 | 2,306 | 32,873 | 38,181 | (14 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Provision for credit losses | 173 | 201 | 3,072 | 10,962 | 245 | 484 | 3,490 | 11,647 | (70 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Goodwill impairment | — | — | — | 10,400 | — | — | — | 10,400 | n/m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All other noninterest expense | 10,578 | 11,150 | 5,961 | 5,901 | 1,165 | 1,128 | 17,704 | 18,179 | (3 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Income (loss) before income taxes | 1,938 | 2,211 | 9,083 | (4,950 | ) | 658 | 694 | 11,679 | (2,045 | ) | n/m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Income tax expense (FTE basis) | 711 | 820 | 3,272 | 2,012 | 244 | 257 | 4,227 | 3,089 | 37 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Net income (loss) | $ | 1,227 | $ | 1,391 | $ | 5,811 | $ | (6,962 | ) | $ | 414 | $ | 437 | $ | 7,452 | $ | (5,134 | ) | n/m | ||||||||||||||||

Net interest yield (FTE basis) | 2.02 | % | 2.00 | % | 9.04 | % | 9.85 | % | 3.23 | % | 4.11 | % | 4.45 | % | 5.09 | % | |||||||||||||||||||

Return on average allocated equity | 5.17 | 5.74 | 27.50 | n/m | 5.15 | 5.51 | 14.09 | n/m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Return on average economic capital (1) | 21.26 | 22.44 | 55.30 | 23.75 | 6.97 | 7.49 | 33.55 | 19.91 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) | 83.36 | 82.21 | 32.90 | 73.06 | 56.36 | 48.89 | 53.86 | 74.85 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Efficiency ratio, excluding goodwill impairment charge (FTE basis) | 83.36 | 82.21 | 32.90 | 26.45 | 56.36 | 48.89 | 53.86 | 47.61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | n/m | n/m | $ | 126,083 | $ | 145,081 | $ | 26,889 | $ | 29,977 | $ | 153,641 | $ | 175,746 | (13 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||

Total earning assets (2) | $ | 419,444 | $ | 413,595 | 127,258 | 146,303 | 43,542 | 39,210 | 480,039 | 477,269 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total assets (2) | 445,922 | 440,030 | 130,254 | 150,660 | 51,553 | 47,660 | 517,523 | 516,511 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total deposits | 421,106 | 414,877 | n/m | n/m | 40,679 | 36,466 | 462,087 | 451,553 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Allocated equity | 23,735 | 24,222 | 21,127 | 32,416 | 8,046 | 7,940 | 52,908 | 64,578 | (18 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economic capital (1) | 5,786 | 6,247 | 10,538 | 14,772 | 5,949 | 5,841 | 22,273 | 26,860 | (17 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Year end | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | n/m | n/m | $ | 120,668 | $ | 137,024 | $ | 25,006 | $ | 28,313 | $ | 146,378 | $ | 166,007 | (12 | ) | |||||||||||||||||||

Total earning assets (2) | $ | 418,622 | $ | 414,215 | 121,991 | 138,071 | 46,515 | 39,697 | 480,378 | 475,716 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total assets (2) | 445,680 | 440,953 | 127,623 | 138,479 | 53,949 | 47,820 | 520,503 | 510,986 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total deposits | 421,871 | 415,189 | n/m | n/m | 41,518 | 37,379 | 464,263 | 452,871 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(1) | Return on average economic capital and economic capital are non-GAAP financial measures. For additional information on these measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and for corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Statistical Table XVI. |

(2) | For presentation purposes, in segments where the total of liabilities and equity exceeds assets, we allocate assets to match liabilities. As a result, total earning assets and total assets of the businesses may not equal total CBB. |

Bank of America 2011 17 | ||

18 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 19 | ||

2011 | |||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | Home Loans | Legacy Assets & Servicing | Total Consumer Real Estate Services | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 1,828 | $ | 1,379 | $ | 3,207 | $ | 4,662 | (31 | )% | |||||||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||||||||||

Mortgage banking income (loss) | 2,502 | (10,695 | ) | (8,193 | ) | 3,164 | n/m | ||||||||||||

Insurance income | 750 | — | 750 | 2,061 | (64 | ) | |||||||||||||

All other income | 972 | 110 | 1,082 | 442 | 145 | ||||||||||||||

Total noninterest income (loss) | 4,224 | (10,585 | ) | (6,361 | ) | 5,667 | n/m | ||||||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 6,052 | (9,206 | ) | (3,154 | ) | 10,329 | n/m | ||||||||||||

Provision for credit losses | 234 | 4,290 | 4,524 | 8,490 | (47 | ) | |||||||||||||

Goodwill impairment | — | 2,603 | 2,603 | 2,000 | 30 | ||||||||||||||

All other noninterest expense | 4,659 | 14,542 | 19,201 | 12,806 | 50 | ||||||||||||||

Income (loss) before income taxes | 1,159 | (30,641 | ) | (29,482 | ) | (12,967 | ) | 127 | |||||||||||

Income tax expense (benefit) (FTE basis) | 426 | (10,435 | ) | (10,009 | ) | (4,070 | ) | 146 | |||||||||||

Net income (loss) | $ | 733 | $ | (20,206 | ) | $ | (19,473 | ) | $ | (8,897 | ) | 119 | |||||||

Net interest yield (FTE basis) | 2.59 | % | 1.64 | % | 2.07 | % | 2.52 | % | |||||||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) | 76.98 | n/m | n/m | n/m | |||||||||||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 54,783 | $ | 65,037 | $ | 119,820 | $ | 129,234 | (7 | ) | |||||||||

Total earning assets | 70,613 | 84,277 | 154,890 | 185,344 | (16 | ) | |||||||||||||

Total assets | 71,644 | 118,723 | 190,367 | 224,994 | (15 | ) | |||||||||||||

Allocated equity | n/a | n/a | 16,202 | 26,016 | (38 | ) | |||||||||||||

Economic capital (1) | n/a | n/a | 14,852 | 21,214 | (30 | ) | |||||||||||||

Year end | |||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 52,371 | $ | 59,988 | $ | 112,359 | $ | 122,933 | (9 | ) | |||||||||

Total earning assets | 58,823 | 73,558 | 132,381 | 172,082 | (23 | ) | |||||||||||||

Total assets | 59,660 | 104,052 | 163,712 | 212,412 | (23 | ) | |||||||||||||

(1) | Average economic capital is a non-GAAP financial measure. For additional information on these measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and for corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Statistical Table XVI. |

20 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 21 | ||

Mortgage Banking Income | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Production loss: | |||||||

Core production revenue | $ | 2,797 | $ | 6,182 | |||

Representations and warranties provision | (15,591 | ) | (6,785 | ) | |||

Total production loss | (12,794 | ) | (603 | ) | |||

Servicing income: | |||||||

Servicing fees | 5,959 | 6,475 | |||||

Impact of customer payments (1) | (2,621 | ) | (3,759 | ) | |||

Fair value changes of MSRs, net of economic hedge results (2) | 656 | 376 | |||||

Other servicing-related revenue | 607 | 675 | |||||

Total net servicing income | 4,601 | 3,767 | |||||

Total CRES mortgage banking income (loss) | (8,193 | ) | 3,164 | ||||

Eliminations (3) | (637 | ) | (430 | ) | |||

Total consolidated mortgage banking income (loss) | $ | (8,830 | ) | $ | 2,734 | ||

(1) | Represents the change in the market value of the MSR asset due to the impact of customer payments received during the year. |

(2) | Includes sale of MSRs. |

(3) | Includes the effect of transfers of mortgage loans from CRES to the ALM portfolio in All Other. |

22 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Key Statistics | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions, except as noted) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Loan production | ||||||||

CRES: | ||||||||

First mortgage | $ | 139,273 | $ | 287,236 | ||||

Home equity | 3,694 | 7,626 | ||||||

Total Corporation (1): | ||||||||

First mortgage | 151,756 | 298,038 | ||||||

Home equity | 4,388 | 8,437 | ||||||

Year end | ||||||||

Mortgage servicing portfolio (in billions) (2) | $ | 1,763 | $ | 2,057 | ||||

Mortgage loans serviced for investors (in billions) | 1,379 | 1,628 | ||||||

Mortgage servicing rights: | ||||||||

Balance | 7,378 | 14,900 | ||||||

Capitalized mortgage servicing rights (% of loans serviced for investors) | 54 | bps | 92 | bps | ||||

(1) | In addition to loan production in CRES, the remaining first mortgage and home equity loan production is primarily in GWIM. |

(2) | Servicing of residential mortgage loans, home equity lines of credit, home equity loans and discontinued real estate mortgage loans. |

Bank of America 2011 23 | ||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 9,490 | $ | 10,064 | (6 | )% | |||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||

Service charges | 3,425 | 3,656 | (6 | ) | |||||||

Investment banking fees | 3,061 | 2,982 | 3 | ||||||||

All other income | 1,342 | 1,046 | 28 | ||||||||

Total noninterest income | 7,828 | 7,684 | 2 | ||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 17,318 | 17,748 | (2 | ) | |||||||

Provision for credit losses | (1,118 | ) | 1,298 | n/m | |||||||

Noninterest expense | 8,888 | 8,672 | 2 | ||||||||

Income before income taxes | 9,548 | 7,778 | 23 | ||||||||

Income tax expense (FTE basis) | 3,501 | 2,887 | 21 | ||||||||

Net income | $ | 6,047 | $ | 4,891 | 24 | ||||||

Net interest yield (FTE basis) | 3.26 | % | 3.76 | % | |||||||

Return on average allocated equity | 12.76 | 9.22 | |||||||||

Return on average economic capital (1) | 26.59 | 17.47 | |||||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) | 51.32 | 48.86 | |||||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 265,560 | $ | 260,970 | 2 | ||||||

Total earning assets | 291,234 | 267,325 | 9 | ||||||||

Total assets | 337,780 | 312,809 | 8 | ||||||||

Total deposits | 237,193 | 203,459 | 17 | ||||||||

Allocated equity | 47,384 | 53,056 | (11 | ) | |||||||

Economic capital (1) | 22,761 | 28,064 | (19 | ) | |||||||

Year end | |||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 278,177 | $ | 254,841 | 9 | ||||||

Total earning assets | 302,353 | 261,902 | 15 | ||||||||

Total assets | 349,473 | 311,113 | 12 | ||||||||

Total deposits | 246,466 | 217,262 | 13 | ||||||||

(1) | Return on average economic capital and economic capital are non-GAAP financial measures. For additional information on these measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and for corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Statistical Table XVI. |

24 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Global Corporate and Commercial Banking | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Global Corporate Banking | Global Commercial Banking | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | |||||||||||||||||

Global Treasury Services | $ | 2,507 | $ | 2,296 | $ | 3,532 | $ | 3,414 | $ | 6,039 | $ | 5,710 | |||||||||||

Business Lending | 3,246 | 3,459 | 4,953 | 5,507 | 8,199 | 8,966 | |||||||||||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense | $ | 5,753 | $ | 5,755 | $ | 8,485 | $ | 8,921 | $ | 14,238 | $ | 14,676 | |||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 101,955 | $ | 85,242 | $ | 162,526 | $ | 173,847 | $ | 264,481 | $ | 259,089 | |||||||||||

Total deposits | 108,630 | 91,108 | 128,513 | 112,173 | 237,143 | 203,281 | |||||||||||||||||

Period end | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 113,979 | $ | 87,570 | $ | 163,256 | $ | 165,725 | $ | 277,235 | $ | 253,295 | |||||||||||

Total deposits | 111,003 | 93,316 | 135,423 | 123,900 | 246,426 | 217,216 | |||||||||||||||||

Investment Banking Fees | |||||||||||||||

Global Banking | Total Corporation | ||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | |||||||||||

Products | |||||||||||||||

Advisory (1) | $ | 1,182 | $ | 934 | $ | 1,248 | $ | 1,019 | |||||||

Debt issuance | 1,294 | 1,433 | 2,888 | 3,267 | |||||||||||

Equity issuance | 585 | 615 | 1,453 | 1,498 | |||||||||||

Gross investment banking fees | 3,061 | 2,982 | 5,589 | 5,784 | |||||||||||

Self-led | (163 | ) | (105 | ) | (372 | ) | (264 | ) | |||||||

Total investment banking fees | $ | 2,898 | $ | 2,877 | $ | 5,217 | $ | 5,520 | |||||||

(1) | Advisory includes fees on debt and equity advisory services and mergers and acquisitions. |

Bank of America 2011 25 | ||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 3,682 | $ | 4,332 | (15 | )% | |||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||

Investment and brokerage services | 2,235 | 2,312 | (3 | ) | |||||||

Investment banking fees | 2,212 | 2,456 | (10 | ) | |||||||

Trading account profits | 6,424 | 9,630 | (33 | ) | |||||||

All other income | 232 | 388 | (40 | ) | |||||||

Total noninterest income | 11,103 | 14,786 | (25 | ) | |||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 14,785 | 19,118 | (23 | ) | |||||||

Provision for credit losses | (56 | ) | 30 | n/m | |||||||

Noninterest expense | 12,236 | 11,769 | 4 | ||||||||

Income before income taxes | 2,605 | 7,319 | (64 | ) | |||||||

Income tax expense (FTE basis) | 1,620 | 3,073 | (47 | ) | |||||||

Net income | $ | 985 | $ | 4,246 | (77 | ) | |||||

Return on average allocated equity | 4.35 | % | 13.01 | % | |||||||

Return on average economic capital (1) | 5.53 | 14.72 | |||||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) | 82.76 | 61.56 | |||||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||

Total trading-related assets (2) | $ | 472,444 | $ | 506,508 | (7 | ) | |||||

Total earning assets (2) | 445,531 | 508,920 | (12 | ) | |||||||

Total assets | 590,428 | 644,674 | (8 | ) | |||||||

Allocated equity | 22,670 | 32,630 | (31 | ) | |||||||

Economic capital (1) | 18,045 | 28,932 | (38 | ) | |||||||

Year end | |||||||||||

Total trading-related assets (2) | $ | 397,876 | $ | 417,157 | (5 | ) | |||||

Total earning assets (2) | 372,852 | 416,315 | (10 | ) | |||||||

Total assets | 501,825 | 537,945 | (7 | ) | |||||||

(1) | Return on average economic capital and economic capital are non-GAAP financial measures. For additional information on these measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and for corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Statistical Table XVI. |

(2) | Trading-related assets include assets which are not considered earning assets (i.e., derivative assets). |

26 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Sales and Trading Revenue (1, 2) | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Sales and trading revenue | |||||||

Fixed income, currencies and commodities | $ | 8,901 | $ | 12,585 | |||

Equity income | 3,943 | 4,101 | |||||

Total sales and trading revenue | $ | 12,844 | $ | 16,686 | |||

Sales and trading revenue, excluding DVA | |||||||

Fixed income, currencies and commodities | $ | 8,107 | $ | 12,383 | |||

Equity income | 3,737 | 4,041 | |||||

Total sales and trading revenue, excluding DVA | $ | 11,844 | $ | 16,424 | |||

(1) | Includes a FTE adjustment of $203 million and $271 million for 2011 and 2010. For additional information on sales and trading revenue, see Note 4 – Derivatives to the Consolidated Financial Statements. |

(2) | Includes Global Banking sales and trading revenue of $273 million and $122 million for 2011 and 2010. |

Credit Default Swaps with Monoline Financial Guarantors | |||||||

December 31 | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Notional | $ | 21,070 | $ | 38,424 | |||

Mark-to-market or guarantor receivable | $ | 1,766 | $ | 9,201 | |||

Credit valuation adjustment | (417 | ) | (5,275 | ) | |||

Total | $ | 1,349 | $ | 3,926 | |||

Credit valuation adjustment % | 24 | % | 57 | % | |||

Gains (losses) | $ | 116 | $ | (24 | ) | ||

Bank of America 2011 27 | ||

28 Bank of America 2011 | ||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 6,052 | $ | 5,682 | 7 | % | |||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||

Investment and brokerage services | 9,310 | 8,660 | 8 | ||||||||

All other income | 2,034 | 1,949 | 4 | ||||||||

Total noninterest income | 11,344 | 10,609 | 7 | ||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 17,396 | 16,291 | 7 | ||||||||

Provision for credit losses | 398 | 646 | (38 | ) | |||||||

Noninterest expense | 14,357 | 13,209 | 9 | ||||||||

Income before income taxes | 2,641 | 2,436 | 8 | ||||||||

Income tax expense (FTE basis) | 969 | 1,083 | (11 | ) | |||||||

Net income | $ | 1,672 | $ | 1,353 | 24 | ||||||

Net interest yield (FTE basis) | 2.24 | % | 2.31 | % | |||||||

Return on average allocated equity | 9.40 | 7.49 | |||||||||

Return on average economic capital (1) | 24.00 | 19.74 | |||||||||

Efficiency ratio (FTE basis) | 82.53 | 81.08 | |||||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 102,144 | $ | 99,269 | 3 | ||||||

Total earning assets | 270,658 | 246,428 | 10 | ||||||||

Total assets | 290,565 | 267,365 | 9 | ||||||||

Total deposits | 254,997 | 232,519 | 10 | ||||||||

Allocated equity | 17,790 | 18,070 | (2 | ) | |||||||

Economic capital (1) | 7,094 | 7,292 | (3 | ) | |||||||

Year end | |||||||||||

Total loans and leases | $ | 103,460 | $ | 100,725 | 3 | ||||||

Total earning assets | 263,586 | 275,520 | (4 | ) | |||||||

Total assets | 284,062 | 296,478 | (4 | ) | |||||||

Total deposits | 253,264 | 258,210 | (2 | ) | |||||||

(1) | Return on average economic capital and economic capital are non-GAAP financial measures. For additional information on these measures, see Supplemental Financial Data on page 15 and for corresponding reconciliations to GAAP financial measures, see Statistical Table XVI. |

Bank of America 2011 29 | ||

Migration Summary | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Average | |||||||

Total deposits – GWIM from / (to) CBB | $ | (2,032 | ) | $ | 2,486 | ||

Total loans – GWIM to CRES and the ALM portfolio | (174 | ) | (1,405 | ) | |||

Year end | |||||||

Total deposits – GWIM from / (to) CBB | $ | (2,918 | ) | $ | 4,881 | ||

Total loans – GWIM to CRES and the ALM portfolio | (299 | ) | (1,625 | ) | |||

Client Balances by Type | |||||||

December 31 | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Assets under management | $ | 647,126 | $ | 643,343 | |||

Brokerage assets | 1,024,193 | 1,064,516 | |||||

Assets in custody | 107,989 | 114,721 | |||||

Deposits | 253,264 | 258,210 | |||||

Loans and leases (1) | 106,672 | 104,213 | |||||

Total client balances | $ | 2,139,244 | $ | 2,185,003 | |||

(1) | Includes margin receivables which are classified in other assets on the Consolidated Balance Sheet. |

30 Bank of America 2011 | ||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | % Change | ||||||||

Net interest income (FTE basis) | $ | 1,780 | $ | 3,655 | (51 | )% | |||||

Noninterest income: | |||||||||||

Card income | 465 | 615 | (24 | ) | |||||||

Equity investment income | 7,044 | 4,574 | 54 | ||||||||

Gains on sales of debt securities | 3,098 | 2,313 | 34 | ||||||||

All other income (loss) | 2,821 | (1,434 | ) | n/m | |||||||

Total noninterest income | 13,428 | 6,068 | 121 | ||||||||

Total revenue, net of interest expense (FTE basis) | 15,208 | 9,723 | 56 | ||||||||

Provision for credit losses | 6,172 | 6,324 | (2 | ) | |||||||

Goodwill impairment | 581 | — | n/m | ||||||||

Merger and restructuring charges | 638 | 1,820 | (65 | ) | |||||||

All other noninterest expense | 4,066 | 4,253 | (4 | ) | |||||||

Income (loss) before income taxes | 3,751 | (2,674 | ) | n/m | |||||||

Income tax benefit (FTE basis) | (1,012 | ) | (3,977 | ) | (75 | ) | |||||

Net income | $ | 4,763 | $ | 1,303 | n/m | ||||||

Balance Sheet | |||||||||||

Average | |||||||||||

Loans and leases: | |||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 227,696 | $ | 210,052 | 8 | ||||||

Credit card | 24,049 | 28,013 | (14 | ) | |||||||

Discontinued real estate | 12,106 | 13,830 | (12 | ) | |||||||

Other | 20,039 | 29,747 | (33 | ) | |||||||

Total loans and leases | 283,890 | 281,642 | 1 | ||||||||

Total assets (1) | 369,659 | 473,253 | (22 | ) | |||||||

Total deposits | 49,267 | 66,882 | (26 | ) | |||||||

Allocated equity (2) | 72,141 | 38,884 | 86 | ||||||||

Year end | |||||||||||

Loans and leases: | |||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 224,654 | $ | 222,299 | 1 | ||||||

Credit card | 14,418 | 27,465 | (48 | ) | |||||||

Discontinued real estate | 11,095 | 13,108 | (15 | ) | |||||||

Other | 17,454 | 22,214 | (21 | ) | |||||||

Total loans and leases | 267,621 | 285,086 | (6 | ) | |||||||

Total assets (1) | 309,471 | 395,975 | (22 | ) | |||||||

Total deposits | 32,729 | 48,767 | (33 | ) | |||||||

(1) | For presentation purposes, in segments where the total of liabilities and equity exceeds assets, which are generally deposit-taking segments, we allocate assets to those segments to match liabilities (i.e., deposits) and allocated equity. Such allocated assets were $497.8 billion and $433.6 billion for 2011 and 2010, and $495.4 billion and $460.1 billion at December 31, 2011 and 2010. The allocation can result in total assets of less than total loans and leases in All Other. |

(2) | Represents the economic capital assigned to All Other as well as the remaining portion of equity not specifically allocated to the business segments. Allocated equity increased due to excess capital not being assigned to the business segments. |

Bank of America 2011 31 | ||

Equity Investments | |||||||

December 31 | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Global Principal Investments | $ | 5,659 | $ | 11,682 | |||

Strategic and other investments | 1,343 | 22,590 | |||||

Total equity investments included in All Other | $ | 7,002 | $ | 34,272 | |||

Equity Investment Income | |||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | |||||

Global Principal Investments | $ | 399 | $ | 2,324 | |||

Strategic and other investments | 6,645 | 2,543 | |||||

Corporate Investments | — | (293 | ) | ||||

Total equity investment income included in All Other | 7,044 | 4,574 | |||||

Total equity investment income included in the business segments | 316 | 686 | |||||

Total consolidated equity investment income | $ | 7,360 | $ | 5,260 | |||

32 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 10 | Long-term Debt and Other Obligations | |||||||||||||||||||

December 31, 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | Due in One Year or Less | Due After One Year Through Three Years | Due After Three Years Through Five Years | Due After Five Years | Total | |||||||||||||||

Long-term debt and capital leases | $ | 97,415 | $ | 93,625 | $ | 48,539 | $ | 132,686 | $ | 372,265 | ||||||||||

Operating lease obligations | 3,008 | 4,573 | 2,903 | 6,117 | 16,601 | |||||||||||||||

Purchase obligations | 7,130 | 4,781 | 3,742 | 4,206 | 19,859 | |||||||||||||||

Time deposits | 133,907 | 14,228 | 6,094 | 3,197 | 157,426 | |||||||||||||||

Other long-term liabilities | 768 | 991 | 753 | 1,128 | 3,640 | |||||||||||||||

Total long-term debt and other obligations | $ | 242,228 | $ | 118,198 | $ | 62,031 | $ | 147,334 | $ | 569,791 | ||||||||||

Bank of America 2011 33 | ||

34 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 35 | ||

36 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 11 | Overview of GSE Balances – 2004-2008 Originations | ||||||||||||||

Legacy Originator | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in billions) | Countrywide | Other | Total | Percent of Total | |||||||||||

Original funded balance | $ | 846 | $ | 272 | $ | 1,118 | |||||||||

Principal payments | (452 | ) | (153 | ) | (605 | ) | |||||||||

Defaults | (56 | ) | (9 | ) | (65 | ) | |||||||||

Total outstanding balance at December 31, 2011 | $ | 338 | $ | 110 | $ | 448 | |||||||||

Outstanding principal balance 180 days or more past due (severely delinquent) | $ | 50 | $ | 12 | $ | 62 | |||||||||

Defaults plus severely delinquent | 106 | 21 | 127 | ||||||||||||

Payments made by borrower: | |||||||||||||||

Less than 13 | $ | 15 | 12 | % | |||||||||||

13-24 | 30 | 23 | |||||||||||||

25-36 | 34 | 27 | |||||||||||||

More than 36 | 48 | 38 | |||||||||||||

Total payments made by borrower | $ | 127 | 100 | % | |||||||||||

Outstanding GSE representations and warranties claims (all vintages) | |||||||||||||||

As of December 31, 2010 | $ | 2.8 | |||||||||||||

As of December 31, 2011 | 6.3 | ||||||||||||||

Cumulative GSE representations and warranties losses (2004-2008 vintages) | $ | 9.2 | |||||||||||||

Bank of America 2011 37 | ||

38 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 12 | Overview of Non-Agency Securitization and Whole Loan Balances | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Principal Balance | Defaulted or Severely Delinquent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in billions) By Entity | Original Principal Balance | Outstanding Principal Balance December 31, 2011 | Outstanding Principal Balance 180 Days or More Past Due | Defaulted Principal Balance | Defaulted or Severely Delinquent | Borrower Made less than 13 Payments | Borrower Made 13 to 24 Payments | Borrower Made 25 to 36 Payments | Borrower Made more than 36 Payments | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bank of America | $ | 100 | $ | 28 | $ | 5 | $ | 4 | $ | 9 | $ | 1 | $ | 2 | $ | 2 | $ | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

Countrywide | 716 | 252 | 84 | 100 | 184 | 24 | 45 | 46 | 69 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Merrill Lynch | 65 | 19 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

First Franklin | 82 | 21 | 7 | 21 | 28 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 13 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total (1, 2) | $ | 963 | $ | 320 | $ | 102 | $ | 137 | $ | 239 | $ | 32 | $ | 57 | $ | 56 | $ | 94 | ||||||||||||||||||

By Product | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prime | $ | 302 | $ | 102 | $ | 17 | $ | 15 | $ | 32 | $ | 2 | $ | 6 | $ | 7 | $ | 17 | ||||||||||||||||||

Alt-A | 172 | 71 | 20 | 28 | 48 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pay option | 150 | 56 | 28 | 28 | 56 | 5 | 14 | 16 | 21 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subprime | 245 | 74 | 34 | 49 | 83 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 31 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home Equity | 88 | 15 | 1 | 16 | 17 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | — | 1 | — | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total | $ | 963 | $ | 320 | $ | 102 | $ | 137 | $ | 239 | $ | 32 | $ | 57 | $ | 56 | $ | 94 | ||||||||||||||||||

(1) | Excludes transactions sponsored by Bank of America and Merrill Lynch where no representations or warranties were made. |

(2) | Includes exposures on third-party sponsored transactions related to legacy entity originations. |

Bank of America 2011 39 | ||

40 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 41 | ||

42 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 43 | ||

44 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 45 | ||

46 Bank of America 2011 | ||

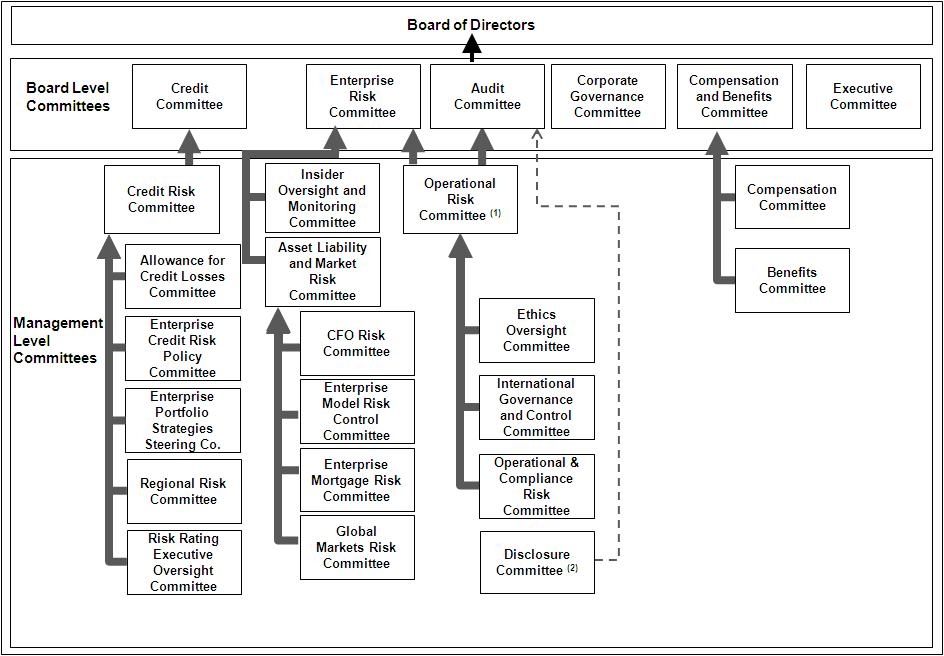

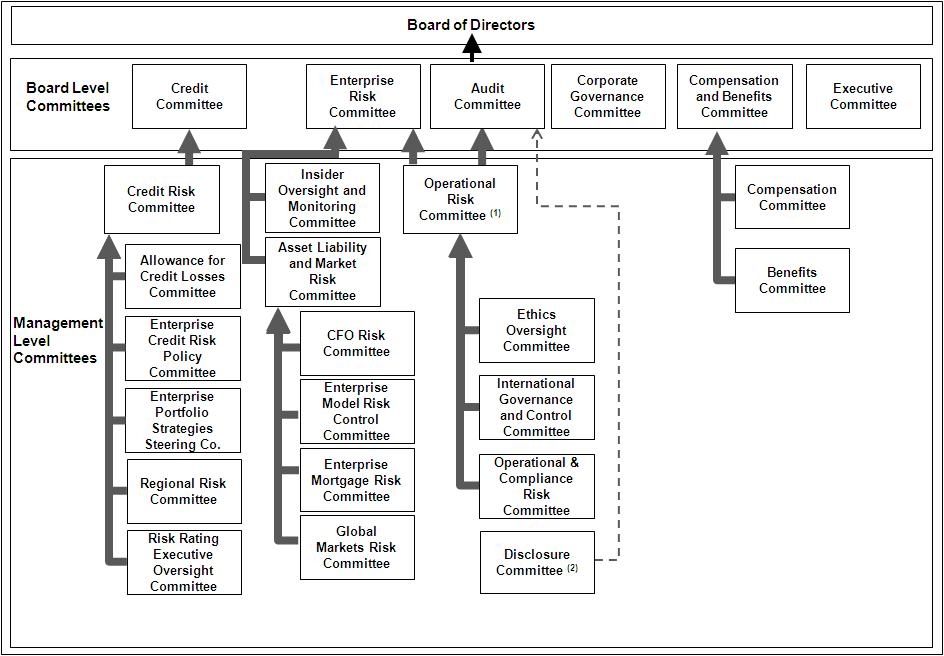

(1) | Compliance Risk activities, including Ethics Oversight, are required to be reviewed by the Audit Committee and Operational Risk activities are required to be reviewed by the Enterprise Risk Committee. |

(2) | The Disclosure Committee assists the CEO and CFO in fulfilling their responsibility for the accuracy and timeliness of the Corporation’s disclosures and reports the results of the process to the Audit Committee. |

Bank of America 2011 47 | ||

48 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 49 | ||

Table 13 | Bank of America Corporation Regulatory Capital | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in billions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Tier 1 common capital ratio | 9.86 | % | 8.60 | % | ||||

Tier 1 capital ratio | 12.40 | 11.24 | ||||||

Total capital ratio | 16.75 | 15.77 | ||||||

Tier 1 leverage ratio | 7.53 | 7.21 | ||||||

Risk-weighted assets | $ | 1,284 | $ | 1,456 | ||||

Adjusted quarterly average total assets (1) | 2,114 | 2,270 | ||||||

(1) | Reflects adjusted average total assets for the three months ended December 31, 2011 and |

Table 14 | Capital Composition | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Total common shareholders’ equity | $ | 211,704 | $ | 211,686 | ||||

Goodwill | (69,967 | ) | (73,861 | ) | ||||

Nonqualifying intangible assets (includes core deposit intangibles, affinity relationships, customer relationships and other intangibles) | (5,848 | ) | (6,846 | ) | ||||

Net unrealized gains or losses on AFS debt and marketable equity securities and net losses on derivatives recorded in accumulated OCI, net-of-tax | 682 | (4,137 | ) | |||||

Unamortized net periodic benefit costs recorded in accumulated OCI, net-of-tax | 4,391 | 3,947 | ||||||

Exclusion of fair value adjustment related to structured liabilities (1) | 944 | 2,984 | ||||||

Disallowed deferred tax asset | (16,799 | ) | (8,663 | ) | ||||

Other | 1,583 | 29 | ||||||

Total Tier 1 common capital | 126,690 | 125,139 | ||||||

Qualifying preferred stock | 15,479 | 16,562 | ||||||

Trust preferred securities | 16,737 | 21,451 | ||||||

Noncontrolling interest | 326 | 474 | ||||||

Total Tier 1 capital | 159,232 | 163,626 | ||||||

Long-term debt qualifying as Tier 2 capital | 38,165 | 41,270 | ||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses | 33,783 | 41,885 | ||||||

Reserve for unfunded lending commitments | 714 | 1,188 | ||||||

Allowance for loan and lease losses exceeding 1.25 percent of risk-weighted assets | (18,159 | ) | (24,690 | ) | ||||

45 percent of the pre-tax net unrealized gains on AFS marketable equity securities | 1 | 4,777 | ||||||

Other | 1,365 | 1,538 | ||||||

Total capital | $ | 215,101 | $ | 229,594 | ||||

(1) | Represents loss on structured liabilities, net-of-tax, that is excluded from Tier 1 common capital, Tier 1 capital and Total capital for regulatory purposes. |

50 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 51 | ||

Table 15 | Bank of America, N.A. and FIA Card Services, N.A. Regulatory Capital | |||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||

2011 | 2010 | |||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | Ratio | Amount | Ratio | Amount | ||||||||||

Tier 1 | ||||||||||||||

Bank of America, N.A. | 11.74 | % | $ | 119,881 | 10.78 | % | $ | 114,345 | ||||||

FIA Card Services, N.A. | 17.63 | 24,660 | 15.30 | 25,589 | ||||||||||

Total | ||||||||||||||

Bank of America, N.A. | 15.17 | 154,885 | 14.26 | 151,255 | ||||||||||

FIA Card Services, N.A. | 19.01 | 26,594 | 16.94 | 28,343 | ||||||||||

Tier 1 leverage | ||||||||||||||

Bank of America, N.A. | 8.65 | 119,881 | 7.83 | 114,345 | ||||||||||

FIA Card Services, N.A. | 14.22 | 24,660 | 13.21 | 25,589 | ||||||||||

52 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 16 | Common Stock Cash Dividend Summary | |||

Declaration Date | Record Date | Payment Date | Dividend Per Share | |

January 11, 2012 | March 2, 2012 | March 23, 2012 | $0.01 | |

November 18, 2011 | December 2, 2011 | December 23, 2011 | 0.01 | |

August 22, 2011 | September 2, 2011 | September 23, 2011 | 0.01 | |

May 11, 2011 | June 3, 2011 | June 24, 2011 | 0.01 | |

January 26, 2011 | March 4, 2011 | March 25, 2011 | 0.01 | |

Bank of America 2011 53 | ||

Table 17 | Global Excess Liquidity Sources | Average for Three Months Ended December 31, | |||||||||

December 31 | |||||||||||

(Dollars in billions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | ||||||||

Parent company | $ | 125 | $ | 121 | $ | 118 | |||||

Bank subsidiaries | 222 | 180 | 215 | ||||||||

Broker/dealers | 31 | 35 | 29 | ||||||||

Total global excess liquidity sources | $ | 378 | $ | 336 | $ | 362 | |||||

Table 18 | Global Excess Liquidity Sources Composition | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in billions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Cash on deposit | $ | 79 | $ | 80 | ||||

U.S. treasuries | 48 | 65 | ||||||

U.S. agency securities and mortgage-backed securities | 228 | 174 | ||||||

Non-U.S. government and supranational securities | 23 | 17 | ||||||

Total global excess liquidity sources | $ | 378 | $ | 336 | ||||

54 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 19 | Long-term Debt by Major Currency | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

U.S. Dollar | $ | 255,262 | $ | 302,487 | ||||

Euro | 68,799 | 87,482 | ||||||

Japanese Yen | 19,568 | 19,901 | ||||||

British Pound | 12,554 | 16,505 | ||||||

Australian Dollar | 4,900 | 6,924 | ||||||

Canadian Dollar | 4,621 | 6,628 | ||||||

Swiss Franc | 2,268 | 3,069 | ||||||

Other | 4,293 | 5,435 | ||||||

Total long-term debt | $ | 372,265 | $ | 448,431 | ||||

Bank of America 2011 55 | ||

56 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Bank of America 2011 57 | ||

58 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 20 | Consumer Loans | |||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||

Outstandings | Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loan Portfolio | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Residential mortgage (1) | $ | 262,290 | $ | 257,973 | $ | 9,966 | $ | 10,592 | ||||||||

Home equity | 124,699 | 137,981 | 11,978 | 12,590 | ||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate (2) | 11,095 | 13,108 | 9,857 | 11,652 | ||||||||||||

U.S. credit card | 102,291 | 113,785 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Non-U.S. credit card | 14,418 | 27,465 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Direct/Indirect consumer (3) | 89,713 | 90,308 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Other consumer (4) | 2,688 | 2,830 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Consumer loans excluding loans accounted for under the fair value option | 607,194 | 643,450 | 31,801 | 34,834 | ||||||||||||

Loans accounted for under the fair value option (5) | 2,190 | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Total consumer loans | $ | 609,384 | $ | 643,450 | $ | 31,801 | $ | 34,834 | ||||||||

(1) | Outstandings includes non-U.S. residential mortgages of $85 million and $90 million at December 31, 2011 and 2010. |

(2) | Outstandings includes $9.9 billion and $11.8 billion of pay option loans and $1.2 billion and $1.3 billion of subprime loans at December 31, 2011 and 2010. We no longer originate these products. |

(3) | Outstandings includes dealer financial services loans of $43.0 billion and $43.3 billion, consumer lending loans of $8.0 billion and $12.4 billion, U.S. securities-based lending margin loans of $23.6 billion and $16.6 billion, student loans of $6.0 billion and $6.8 billion, non-U.S. consumer loans of $7.6 billion and $8.0 billion, and other consumer loans of $1.5 billion and $3.2 billion at December 31, 2011 and 2010. |

(4) | Outstandings includes consumer finance loans of $1.7 billion and $1.9 billion, other non-U.S. consumer loans of $929 million and $803 million, and consumer overdrafts of $103 million and $88 million at December 31, 2011 and 2010. |

(5) | Consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option include residential mortgage loans of $906 million and discontinued real estate loans of $1.3 billion at December 31, 2011. There were no consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2010. See Consumer Credit Risk – Consumer Loans Accounted for Under the Fair Value Option on page 69 and Note 23 – Fair Value Option to the Consolidated Financial Statements for additional information on the fair value option. |

Table 21 | Consumer Credit Quality | |||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||

Accruing Past Due 90 Days or More | Nonperforming | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Residential mortgage (1) | $ | 21,164 | $ | 16,768 | $ | 15,970 | $ | 17,691 | ||||||||

Home equity | — | — | 2,453 | 2,694 | ||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate | — | — | 290 | 331 | ||||||||||||

U.S. credit card | 2,070 | 3,320 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Non-U.S. credit card | 342 | 599 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Direct/Indirect consumer | 746 | 1,058 | 40 | 90 | ||||||||||||

Other consumer | 2 | 2 | 15 | 48 | ||||||||||||

Total (2) | $ | 24,324 | $ | 21,747 | $ | 18,768 | $ | 20,854 | ||||||||

Consumer loans as a percentage of outstanding consumer loans (2) | 4.01 | % | 3.38 | % | 3.09 | % | 3.24 | % | ||||||||

Consumer loans as a percentage of outstanding loans excluding Countrywide PCI and fully-insured loan portfolios (2) | 0.66 | 0.92 | 3.90 | 3.85 | ||||||||||||

(1) | Balances accruing past due 90 days or more are fully-insured loans. These balances include $17.0 billion and $8.3 billion of loans on which interest has been curtailed by the FHA, and therefore are no longer accruing interest, although principal is still insured and $4.2 billion and $8.5 billion of loans on which interest was still accruing at December 31, 2011 and 2010. |

(2) | Balances exclude consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option. At December 31, 2011, approximately $713 million of loans accounted for under the fair value option were past due 90 days or more and not accruing interest. There were no consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2010. |

Bank of America 2011 59 | ||

Table 22 | Consumer Net Charge-offs and Related Ratios | |||||||||||||

Net Charge-offs | Net Charge-off Ratios (1) | |||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 3,832 | $ | 3,670 | 1.45 | % | 1.49 | % | ||||||

Home equity | 4,473 | 6,781 | 3.42 | 4.65 | ||||||||||

Discontinued real estate | 92 | 68 | 0.75 | 0.49 | ||||||||||

U.S. credit card | 7,276 | 13,027 | 6.90 | 11.04 | ||||||||||

Non-U.S. credit card | 1,169 | 2,207 | 4.86 | 7.88 | ||||||||||

Direct/Indirect consumer | 1,476 | 3,336 | 1.64 | 3.45 | ||||||||||

Other consumer | 202 | 261 | 7.32 | 8.89 | ||||||||||

Total | $ | 18,520 | $ | 29,350 | 2.94 | 4.51 | ||||||||

(1) | Net charge-off ratios are calculated as net charge-offs divided by average outstanding loans excluding loans accounted for under the fair value option. |

Ÿ | Discontinued real estate loans including subprime and pay option |

Ÿ | Residential mortgage loans and home equity loans for products we no longer originate including reduced document loans and interest-only loans not underwritten to fully amortizing payment |

Ÿ | Loans that would not have been originated under our underwriting standards at December 31, 2010 including conventional loans with an original loan-to-value (LTV) greater than 95 percent and government-insured loans for which the borrower has a FICO score less than 620 |

Ÿ | Countrywide PCI loan portfolios |

Ÿ | Certain loans that met a pre-defined delinquency and probability of default threshold as of January 1, 2011 |

Table 23 | Home Loans Portfolio | |||||||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Outstandings | Nonperforming | Net Charge-offs | ||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | |||||||||||||||

Core portfolio | ||||||||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 178,337 | $ | 166,927 | $ | 2,414 | $ | 1,510 | $ | 348 | ||||||||||

Home equity | 67,055 | 71,519 | 439 | 107 | 501 | |||||||||||||||

Legacy Assets & Servicing portfolio | ||||||||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage (1) | 83,953 | 91,046 | 13,556 | 16,181 | 3,484 | |||||||||||||||

Home equity | 57,644 | 66,462 | 2,014 | 2,587 | 3,972 | |||||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate (1) | 11,095 | 13,108 | 290 | 331 | 92 | |||||||||||||||

Home loans portfolio | ||||||||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage | 262,290 | 257,973 | 15,970 | 17,691 | 3,832 | |||||||||||||||

Home equity | 124,699 | 137,981 | 2,453 | 2,694 | 4,473 | |||||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate | 11,095 | 13,108 | 290 | 331 | 92 | |||||||||||||||

Total home loans portfolio | $ | 398,084 | $ | 409,062 | $ | 18,713 | $ | 20,716 | $ | 8,397 | ||||||||||

(1) | Balances exclude consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option of $906 million for residential mortgage loans and $1.3 billion for discontinued real estate loans at December 31, 2011. There were no consumer loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2010. See Note 23 – Fair Value Option to the Consolidated Financial Statements for additional information on the fair value option. |

60 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 24 | Residential Mortgage – Key Credit Statistics | |||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||

Reported Basis (1) | Excluding Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired and Fully-insured Loans | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Outstandings | $ | 262,290 | $ | 257,973 | $ | 158,470 | $ | 180,136 | ||||||||

Accruing past due 30 days or more | 28,688 | 24,267 | 3,950 | 5,117 | ||||||||||||

Accruing past due 90 days or more | 21,164 | 16,768 | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

Nonperforming loans | 15,970 | 17,691 | 15,970 | 17,691 | ||||||||||||

Percent of portfolio | ||||||||||||||||

Refreshed LTV greater than 90 but less than 100 | 15 | % | 15 | % | 11 | % | 11 | % | ||||||||

Refreshed LTV greater than 100 | 33 | 32 | 26 | 24 | ||||||||||||

Refreshed FICO below 620 | 21 | 20 | 15 | 15 | ||||||||||||

2006 and 2007 vintages (2) | 27 | 32 | 37 | 40 | ||||||||||||

Net charge-off ratio (3) | 1.45 | 1.49 | 2.27 | 1.86 | ||||||||||||

(1) | Outstandings, accruing past due, nonperforming loans and percentages of portfolio exclude loans accounted for under the fair value option. There were no residential mortgage loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2010. See Note 23 – Fair Value Option to the Consolidated Financial Statements for additional information on the fair value option. |

(2) | These vintages of loans account for 63 percent and 67 percent of nonperforming residential mortgage loans at December 31, 2011 and 2010. These vintages of loans accounted for 73 percent and 77 percent of residential mortgage net charge-offs in 2011 and 2010. |

(3) | Net charge-off ratios are calculated as net charge-offs divided by average outstanding loans, excluding loans accounted for under the fair value option. |

Bank of America 2011 61 | ||

Table 25 | Residential Mortgage State Concentrations | |||||||||||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Outstandings (1) | Nonperforming (1) | Net Charge-offs | ||||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||

California | $ | 54,203 | $ | 63,677 | $ | 5,606 | $ | 6,389 | $ | 1,326 | $ | 1,392 | ||||||||||||

Florida | 12,338 | 13,298 | 1,900 | 2,054 | 595 | 604 | ||||||||||||||||||

New York | 11,539 | 12,198 | 838 | 772 | 106 | 44 | ||||||||||||||||||

Texas | 7,525 | 8,466 | 425 | 492 | 55 | 52 | ||||||||||||||||||

Virginia | 5,709 | 6,441 | 399 | 450 | 64 | 72 | ||||||||||||||||||

Other U.S./Non-U.S. | 67,156 | 76,056 | 6,802 | 7,534 | 1,686 | 1,506 | ||||||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage loans (2) | $ | 158,470 | $ | 180,136 | $ | 15,970 | $ | 17,691 | $ | 3,832 | $ | 3,670 | ||||||||||||

Fully-insured loan portfolio | 93,854 | 67,245 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Countrywide purchased credit-impaired residential mortgage loan portfolio | 9,966 | 10,592 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Total residential mortgage loan portfolio | $ | 262,290 | $ | 257,973 | ||||||||||||||||||||

(1) | Outstandings and nonperforming amounts exclude loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2011. There were no residential mortgage loans accounted for under the fair value option at December 31, 2010. See Note 23 – Fair Value Option to the Consolidated Financial Statements for additional information on the fair value option. |

(2) | Amount excludes the Countrywide PCI residential mortgage and fully-insured loan portfolios. |

62 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 26 | Home Equity – Key Credit Statistics | |||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||

Reported Basis | Excluding Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loans | |||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

Outstandings | $ | 124,699 | $ | 137,981 | $ | 112,721 | $ | 125,391 | ||||||||

Accruing past due 30 days or more (1) | 1,658 | 1,929 | 1,658 | 1,929 | ||||||||||||

Nonperforming loans (1) | 2,453 | 2,694 | 2,453 | 2,694 | ||||||||||||

Percent of portfolio | ||||||||||||||||

Refreshed combined LTV greater than 90 but less than 100 | 10 | % | 11 | % | 11 | % | 11 | % | ||||||||

Refreshed combined LTV greater than 100 | 36 | 34 | 32 | 30 | ||||||||||||

Refreshed FICO below 620 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 12 | ||||||||||||

2006 and 2007 vintages (2) | 50 | 50 | 46 | 47 | ||||||||||||

Net charge-off ratio (3) | 3.42 | 4.65 | 3.77 | 5.10 | ||||||||||||

(1) | Accruing past due 30 days or more includes $609 million and $662 million and nonperforming loans includes $703 million and $480 million of loans where we serviced the underlying first-lien at December 31, 2011 and 2010. |

(2) | These vintages of loans have higher refreshed combined LTV ratios and accounted for 54 percent and 57 percent of nonperforming home equity loans at December 31, 2011 and 2010. These vintages of loans accounted for 65 percent and 66 percent of net charge-offs in 2011 and 2010. |

(3) | Net charge-off ratios are calculated as net charge-offs divided by average outstanding loans. |

Bank of America 2011 63 | ||

64 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 27 | Home Equity State Concentrations | |||||||||||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Outstandings | Nonperforming | Net Charge-offs | ||||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||

California | $ | 32,398 | $ | 35,426 | $ | 627 | $ | 708 | $ | 1,481 | $ | 2,341 | ||||||||||||

Florida | 13,450 | 15,028 | 411 | 482 | 853 | 1,420 | ||||||||||||||||||

New Jersey | 7,483 | 8,153 | 175 | 169 | 164 | 219 | ||||||||||||||||||

New York | 7,423 | 8,061 | 242 | 246 | 196 | 273 | ||||||||||||||||||

Massachusetts | 4,919 | 5,657 | 67 | 71 | 71 | 102 | ||||||||||||||||||

Other U.S./Non-U.S. | 47,048 | 53,066 | 931 | 1,018 | 1,708 | 2,426 | ||||||||||||||||||

Home equity loans (1) | $ | 112,721 | $ | 125,391 | $ | 2,453 | $ | 2,694 | $ | 4,473 | $ | 6,781 | ||||||||||||

Countrywide purchased credit-impaired home equity portfolio | 11,978 | 12,590 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Total home equity loan portfolio | $ | 124,699 | $ | 137,981 | ||||||||||||||||||||

(1) | Amount excludes the Countrywide PCI home equity loan portfolio. |

Bank of America 2011 65 | ||

Table 28 | Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loan Portfolio | ||||||||||||||||||

December 31, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | Unpaid Principal Balance | Carrying Value | Related Valuation Allowance | Carrying Value Net of Valuation Allowance | % of Unpaid Principal Balance | ||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 10,426 | $ | 9,966 | $ | 1,331 | $ | 8,635 | 82.82 | % | |||||||||

Home equity | 12,516 | 11,978 | 5,129 | 6,849 | 54.72 | ||||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate | 11,891 | 9,857 | 1,999 | 7,858 | 66.08 | ||||||||||||||

Total Countrywide purchased credit-impaired loan portfolio | $ | 34,833 | $ | 31,801 | $ | 8,459 | $ | 23,342 | 67.01 | ||||||||||

December 31, 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||

Residential mortgage | $ | 11,481 | $ | 10,592 | $ | 663 | $ | 9,929 | 86.48 | % | |||||||||

Home equity | 15,072 | 12,590 | 4,467 | 8,123 | 53.89 | ||||||||||||||

Discontinued real estate | 14,893 | 11,652 | 1,204 | 10,448 | 70.15 | ||||||||||||||

Total Countrywide purchased credit-impaired loan portfolio | $ | 41,446 | $ | 34,834 | $ | 6,334 | $ | 28,500 | 68.76 | ||||||||||

Table 29 | Outstanding Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loan Portfolio – Residential Mortgage State Concentrations | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

California | $ | 5,535 | $ | 5,882 | ||||

Florida | 757 | 779 | ||||||

Virginia | 532 | 579 | ||||||

Maryland | 258 | 271 | ||||||

Texas | 130 | 164 | ||||||

Other U.S./Non-U.S. | 2,754 | 2,917 | ||||||

Total Countrywide purchased credit-impaired residential mortgage loan portfolio | $ | 9,966 | $ | 10,592 | ||||

66 Bank of America 2011 | ||

Table 30 | Outstanding Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loan Portfolio – Home Equity State Concentrations | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

California | $ | 3,999 | $ | 4,178 | ||||

Florida | 734 | 750 | ||||||

Arizona | 501 | 520 | ||||||

Virginia | 496 | 532 | ||||||

Colorado | 337 | 375 | ||||||

Other U.S./Non-U.S. | 5,911 | 6,235 | ||||||

Total Countrywide purchased credit-impaired home equity portfolio | $ | 11,978 | $ | 12,590 | ||||

Table 31 | Outstanding Countrywide Purchased Credit-impaired Loan Portfolio – Discontinued Real Estate State Concentrations | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

California | $ | 5,262 | $ | 6,322 | ||||

Florida | 958 | 1,121 | ||||||

Washington | 331 | 368 | ||||||

Virginia | 277 | 344 | ||||||

Arizona | 251 | 339 | ||||||

Other U.S./Non-U.S. | 2,778 | 3,158 | ||||||

Total Countrywide purchased credit-impaired discontinued real estate loan portfolio | $ | 9,857 | $ | 11,652 | ||||

Table 32 | U.S. Credit Card – Key Credit Statistics | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Outstandings | $ | 102,291 | $ | 113,785 | ||||

Accruing past due 30 days or more | 3,823 | 5,913 | ||||||

Accruing past due 90 days or more | 2,070 | 3,320 | ||||||

2011 | 2010 | |||||||

Net charge-offs | $ | 7,276 | $ | 13,027 | ||||

Net charge-off ratios (1) | 6.90 | % | 11.04 | % | ||||

(1) | Net charge-off ratios are calculated as net charge-offs divided by average outstanding loans and leases. |

Bank of America 2011 67 | ||

Table 33 | U.S. Credit Card State Concentrations | |||||||||||||||||||||||

December 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Outstandings | Accruing Past Due 90 Days or More | Net Charge-offs | ||||||||||||||||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||

California | $ | 15,246 | $ | 17,028 | $ | 352 | $ | 612 | $ | 1,402 | $ | 2,752 | ||||||||||||

Florida | 7,999 | 9,121 | 221 | 376 | 838 | 1,611 | ||||||||||||||||||

Texas | 6,885 | 7,581 | 131 | 207 | 429 | 784 | ||||||||||||||||||

New York | 6,156 | 6,862 | 126 | 192 | 403 | 694 | ||||||||||||||||||

New Jersey | 4,183 | 4,579 | 86 | 132 | 275 | 452 | ||||||||||||||||||

Other U.S. | 61,822 | 68,614 | 1,154 | 1,801 | 3,929 | 6,734 | ||||||||||||||||||

Total U.S. credit card portfolio | $ | 102,291 | $ | 113,785 | $ | 2,070 | $ | 3,320 | $ | 7,276 | $ | 13,027 | ||||||||||||

Table 34 | Non-U.S. Credit Card – Key Credit Statistics | |||||||

December 31 | ||||||||

(Dollars in millions) | 2011 | 2010 | ||||||

Outstandings | $ | 14,418 | $ | 27,465 | ||||

Accruing past due 30 days or more | 610 | 1,354 | ||||||

Accruing past due 90 days or more | 342 | 599 | ||||||

2011 | 2010 | |||||||

Net charge-offs | $ | 1,169 | $ | 2,207 | ||||

Net charge-off ratios (1) | 4.86 | % | 7.88 | % | ||||

(1) | Net charge-off ratios are calculated as net charge-offs divided by average outstanding loans and leases. |

68 Bank of America 2011 | ||